Last week, news came that Trove, the National Library of Australia’s fabulous digital repository, was under threat from funding cuts. A flood of users from all walks of life began tweeting their support under the #fundTrove hashtag. (See an article in the Conversation outlining the funding cuts here.) They also shared the reasons why Trove is so valuable to them in their professional and/or everyday lives. It has made for quite

Sydney Morning Herald, 17 Sept. 1913

compelling reading – historians, teachers, novelists, family history buffs, students, all have their unique Trove stories.

For archival researchers, such as myself, Trove is a godsend. Millions of documents are available, it is easily searchable and its scope stretches far beyond the shores of Australia.

I have used Trove, for instance, to find all of the newspaper articles pertaining to the “Sutton Case”, the first organised Franco-Australian blackbirding expedition. You can read about this here. It has also been useful in my research into Reunionese migrants in 19th century New Caledonia as often events that occurred in the Pacific Islands were reported in the Australian press. When a ship came in from the Pacific, any significant events would find their way into the local newspapers.

The great thing about Trove, as with all archival research, is you never know what gems you will unearth. I came across the “Island Crime” story (reproduced above) when looking for information on a Reunionese family (Aymard), who had settled in New Caledonia.

Dated 1913, this article relates a murder that took place in the Vallée des Colons, a quartier of Noumea. While, at first glance, it seems to have little to do with my research, it demonstrates that the French colonial and, more specifically, New Caledonian approach to conceiving of or constructing race that I have discussed here persisted into the the 20th century.

In the article, we learn that an unfortunate “Arab”, El Haoussine ben Cherif, was stabbed in the stomach by a “Javanese” man called Belenguen. Apparently, Belenguen owed ben Cherif 5 francs and, unable to pay him, left his mandolin as security. When the Javanese New Year came round, Belenguen went to ben Cherif to ask for his mandolin. Ben Cherif wanted his 5 francs, an argument ensued and ben Cherif was fatally stabbed. A “neighbour”, Aymard, rushed to the “Arab’s” aid, asking him who had stabbed him. Ben Cherif gurgled the “name of the employer of the Javanese” before taking his last breath. The next day, the “Javanese” was found in the bush with a knife and was arrested.

The evidence appears quite circumstantial and one wonders whether the fact that ben Cherif named the employer of Belenguen as the murderer was ever investigated. One suspects not, given the unquestioning way in which the story was reported and the social status of both victim and alleged killer.

Aside from this judicial question, the interesting thing about this story is the way in which the three men were represented. Two of them were given broad, stereotypical, racial/ethnic labels: “Arab” and “Javanese”, while the other is simply described as a “neighbour”.

Aside from this judicial question, the interesting thing about this story is the way in which the three men were represented. Two of them were given broad, stereotypical, racial/ethnic labels: “Arab” and “Javanese”, while the other is simply described as a “neighbour”.

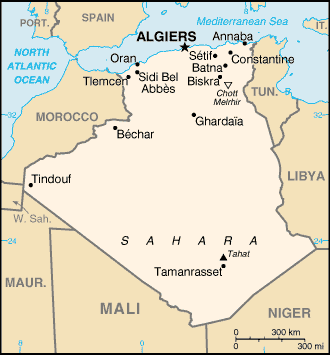

Cheik El Mokrani, leader of the Algerian revolt against the French

The “Arab” was certainly an Algerian. The French deported to New Caledonia around 350 Algerian political prisoners who were captured after a series of revolts against French rule in Algeria 1870-71. Ben Cherif was possibly the son of prisoner no. 845, Brahim ben Cherif, cheik, who arrived as an Algerian déporté on board the Calvados in January 1875. While these déportés are perhaps the most well-known of the Algerian convicts, there were also several thousand others transported to the Pacific before 1897 for run-of-the-mill crimes (theft, insubordination, assault etc.) and this man may well have been one of those. The French referred to Algerians collectively as “Arabs”, despite this not being entirely accurate (Algeria is in North Africa). For an excellent study of the Algerians who ended up spending the rest of their lives exiled in the Pacific, see Ouennoughi (2006).

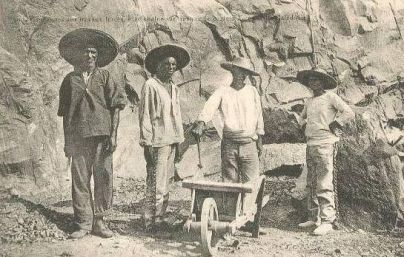

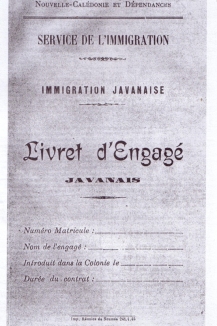

The “Javanese”, Belenguen, would have arrived in New Caledonia as an indentured worker sometime in 1896 or later, when the French began recruiting in Indonesia to meet the labour demands of agriculture, domestic service and mining.

The third man, Aymard, whose neutral, non racialised depiction leads the modern-day Australian reader, conditioned by the questionable habit of some journalists to identify non-white persons by their supposed ethnicity (viz. Polynesian, “of Middle Eastern appearance”, Chinese etc.), to decode as white. Aymard, however, was almost certainly black, of African extraction, son or grandson of enfranchised Reunionese slaves (as neither his first name nor his age is given, it is not entirely clear to which generation he belongs). Why is it that he was not “othered” or racialised in the news story?

Algerian convicts in New Caledonia

The answer has nothing to do with skin colour. Notions of whiteness in New Caledonia (following, to an extent, the lead of Indian Ocean colony, Reunion), were related to citizenship and one’s belonging to the “free” group of settlers. Both the “Arab” and the “Javanese” were racialised due to their “unfree” status (whether or not they were technically free at the time). The “Arab” was likely a convict or son of a convict and the “Javanese” had entered the colony on a contract of indenture. In addition, neither would have had French citizenship. The Algerian would have been classed under the Code de l’Indigénat (Native or Indigenous code) that was in effect in French colonies as a French “subject”.

Photo credit: Le cri du cagou

The Indonesian would have had only his Indonesian citizenship, bound by contract to an employer. As such, these men were excluded from the French/white social group and subject to racist laws. Interestingly, the Algerians, forced to marry local French convict women as no Algerian women were sent to New Caledonia, eventually blended into the local “white’ settler population, although some managed to preserve elements of their culture and in recent times, there have been reconnections with Algeria, books, television documentaries etc.

Aymard, on the other hand, despite outward appearances, belonged to the free settler group by virtue of his French citizenship and was therefore, by default, “white”. When slavery was abolished in the French colonies in 1848, all of the former slaves received French citizenship. French law forbade any mention of the “race” of its citizens in official records and this meant that in a colony like New Caledonia, newcomers from elsewhere in the empire were absorbed into the white settler population. This whitewashing of colonial history was bolstered by the tradition of the non-dit (the unsaid) that enshrouded so-called “undesirable” social backgrounds (slave, convict) in secrecy and silence. In this colonial context, we can clearly see the social construction of “race”.

From this one small article among the currently (as of today’s count) 471,603,782 online resources on Trove, we can learn so much. Trove is not only a national treasure, but a world heritage site! #fundTrove

References

Ouennoughi, Mélica. 2006. Les déportés maghrébins en Nouvelle-Calédonie et la culture du palmier dattier: (1864 à nos jours), Paris: L’Harmattan.

Speedy, Karin. 2012. “From the Indian Ocean to the Pacific: Affranchis and Petits- Blancs in New Caledonia”, Portal Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, Special Issue: Indian Ocean Traffic http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/portal.v9i1.2567

Pingback: This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History – Imperial & Global Forum

I am the editor of the website Le Cri du Cagou and on behalf of the team we thank you for the credit

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Speedy Research & Consulting.

LikeLike